The following book review is brought to you by Northwest Territories Chapter of the Institute of Public Administration of Canada.

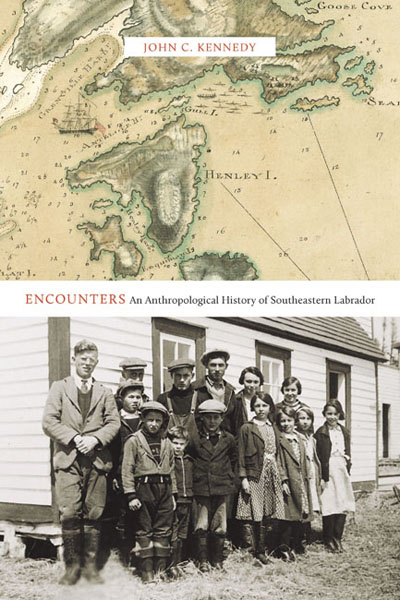

As part of its Book Review Forum, the IPAC NWT Regional Group is pleased to present the following review of John C. Kennedy’s Encounters: An Anthropological History of Southeastern Labrador(McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2015)

Too often it appears that history favours, not the bold, but the banal. Consider, for example, the volume of works chronicling Vimy, the Avro Arrow, and Trudeaumania. These subjects are no doubt worthy of analysis, but perhaps tired in their telling. Contrast those potted plots against what you know about Labrador.

Too often it appears that history favours, not the bold, but the banal. Consider, for example, the volume of works chronicling Vimy, the Avro Arrow, and Trudeaumania. These subjects are no doubt worthy of analysis, but perhaps tired in their telling. Contrast those potted plots against what you know about Labrador.

More intrepid readers may be familiar with Labrador through former Senator Bill Rompkey’s writings, or in the depiction of characters such as Captain George Cartwright and Sir Wilfred Grenfell. Fewer will be informed of how Indigenous peoples, settlers, merchants, marauders, fishers, and bureaucrats encountered one another and how those encounters shaped the settlement, economy, and society of Labrador. This is, in part, what makes John C. Kennedy’s Encounters: An Anthropological History of Southeastern Labrador a valuable contribution to our understanding of Canada.

It is not just the originality of subject that makes Kennedy’s book appealing. Kennedy has devoted a career to this geographic area and to his craft. He documents change in southeastern Labrador and, by extension change, over the entire region from 1763 to present. In doing so, he is chronicling a place that for most Canadians is seldom considered and less often seen. Moreover, Kennedy is a reliable documentarian, building on his lifelong tenure as a student of anthropology. This is further supported by his extensive field work in Labrador 1979 and 2013.

The encounters described by Kennedy are often personal and interwoven. Chapters are devoted to the development of a transient and resident merchant class in the 18thand 19thcenturies; the growth of the fishery as a way of life and export commodity in the 19thand 20thcenturies; patterns of settlement and migration that resulted from these economic activities; and, how centralization and decline have marked more recent times.

The stories that illustrate these encounters give the book meaning. Several themes will be familiar to those resident in other parts of northern Canada: theft, disease, grandiose economic schemes, colonial government administrations, transience, relocation, education, health, and the means of survival. Consider the case of Edward Mercer, who, in the winter of 1868, moved with his family to Sandwich Bay to settle as fishers. By spring, he had buried four of five sons (151). Kennedy also highlights the decision of Captain Cartwright to take an Inuit family of five to England in 1773, to have only one return alive; later, that sole survivor would transmit smallpox to her home community (95-96). He also covers more contemporary stories of relocation schemes, ordered or incentivized by government to ease administrative burden but subsequently disruptive to social, cultural, and linguistic stability. For those with a general appreciation of northern history, the repetition of these sad tales are heartbreaking in their commonality.

Though less an explicit topic, a consistent theme and subtle argument of the book is the extent and degree of ‘Inuitness’ that runs on a continuum from northern to southern Labrador. To the uninitiated, like me, this may seem logical and uncontroversial; however, in an age of studies of land use and occupancy that lead to land claim agreements and the definitions of identity politics, Kennedy’s argument is, for some, contentious. Whereas once people of Inuit heritage, whether mixed or otherwise, actively hid their Indigenous past in defense against prejudice and discrimination, today documented claims to indigeneity can be a source of economic benefit, community recognition, and personal pride. As Kennedy illustrates, these complexities are still being navigated through land claim negotiations and court cases. Kennedy is particularly strong in illustrating the creation of a local Métis peoples as one of the outcomes of centuries of encounters. This is a result not just of mere interactions, but from a ‘transhumance’ specific to the origins of this place (e.g., 285, 317).

Kennedy appears to harbour a dislike of government, especially civil servants. He all too often refers to government employees as ‘distant bureaucrats’ (e.g., 285). This device seems here to be less analytical conclusion and more trope. Although well worn, it does signal, more broadly, a geographic and contemporary reference to power (329). Encounters between peoples in Labrador have often been a struggle for power. This is evident in rivalries between merchants, between merchants and fishers, and between economic actors and government agents. It is also evident between Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples, as well as between Inuit, Innu, and Inuit-Métis. Kennedy appears to view more local autonomy, in whatever form, as the bulwark against inevitable future encounters with outside interests.

I am not an anthropologist, nor have I encountered southeastern Labrador. However, I do recognize many of the themes in this book, and in the history of the people of Labrador as told by Kennedy, as consistent with narratives across the Canadian north. Those with an active role is determining government policy, establishing self-government, or making economic investments in regions of Canada where the types of encounters described by Kennedy are perceptible would do well to observe and consider the history of southeastern Labrador, perhaps beginning by reading Kennedy’s book.

This review was authored by David M. Brock, who is Assistant Deputy Minister, Climate Change & Adaptation, Government of Saskatchewan, and a founder of the IPAC Northwest Territories Regional Group. This review was prepared for Northern Public Affairs magazine by the Institute of Public Administration of Canada’s (IPAC) NWT Regional Group. Please note the views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the policy or position of IPAC. Many thanks to McGill-Queen’s University Press for providing a courtesy copy for our reviewer.